After last week’s article on a proven way to repay your mortgage in Switzerland, I received many kind messages and had a number of very interesting conversations around the idea. Thank you to everyone who reached out — I genuinely enjoyed those exchanges.

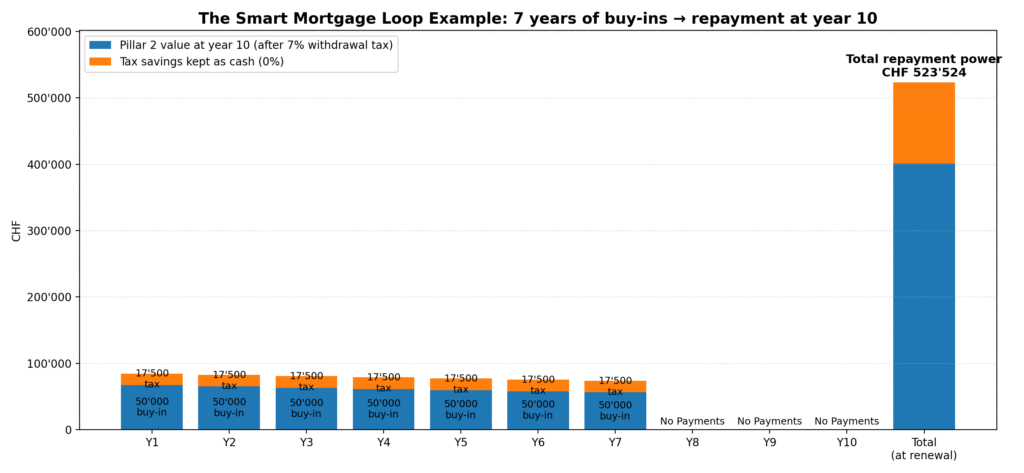

Several of those discussions naturally moved from theory to practice, so I thought it would be useful to share a concrete example showing how the smart mortgage loop can play out over time. Below is a simple visual that brings the numbers together, and here I’ve linked the original article for anyone who’d like to revisit the full framework.

How to read this chart:

Buy-ins in years 1–7.

Three-year waiting period (blocking rule).

Repayment power at renewal.

A real-life example

Examples make this much easier to relate to, so let’s look at one.

Assume I have a CHF 500’000 mortgage tranche, fixed for 10 years. My goal is simple: repay this tranche in full when it comes up for renewal.

If I did this the usual way — by sending after-tax money straight to the bank — I’d need to set aside roughly CHF 50’000 per year for ten years. That’s the straightforward, intuitive approach.

Instead, I use what I call the smart mortgage loop.

For the next seven years, I make a CHF 50’000 buy-in each year into my second pillar. These buy-ins are tax-deductible, so each year I deduct them from my taxable income and pay less in income tax.

After those seven years, nothing dramatic happens. I simply wait. By the time the mortgage comes up for renewal, all contributions satisfy the three-year blocking rule. Close to the renewal date, I withdraw the accumulated amount via WEF, use it to repay the tranche, and pay a 7% capital withdrawal tax on the amount withdrawn.

At this point, many people pause and say:

“Wait a moment — 7 × CHF 50’000 is only CHF 350’000. That doesn’t get you to CHF 500’000.”

Exactly. That’s why the full picture matters.

What this strategy actually produces

Over the ten-year period, this approach produces CHF 431’208 in my second pillar, assuming a modest 3% annual return. After applying the 7% withdrawal tax, that leaves CHF 401’024.

On top of that, the tax deductions along the way amount to CHF 122’500. To stay conservative, I assume those tax savings earn no return at all and simply sit as cash.

Put together, that gives me CHF 523’524 available to repay the mortgage — more than the CHF 500’000 I actually need.

And that already includes a margin of safety. I assumed no return on the tax savings and no particularly strong pension fund performance. In reality, I could have invested the tax savings as well, which would only improve the outcome. But I prefer to think about this strategy in conservative terms: if it works without optimistic assumptions, it works.

What if returns are slightly higher?

Now, let’s briefly relax those assumptions — not to be optimistic, but simply realistic.

If my second pillar earned 4% per year, and I invested the tax savings in a conservative ETF portfolio (for example 50% bonds and 50% equities) that also earned 4%, the picture changes again. At the end of ten years, I would have CHF 591’353 available to repay the mortgage — already after withdrawal tax.

In practice, you might also choose to withdraw the money in two tranches rather than one, especially if your mortgage itself is split — for example CHF 300’000 and CHF 200’000. That’s perfectly possible, as long as you respect the five-year rule: WEF withdrawals can generally be made once every five years.

The key insight

I didn’t save more money.

I didn’t take more risk.

I simply changed the order in which the same money moves through the system.

That sequencing — buy-ins first, deducting taxes, letting the money compound, and only then repaying the mortgage — is what does the heavy lifting.

Try it yourself!

2nd Pillar Buy-In Calculator

Calculate the compound growth and tax benefits of voluntary contributions to your Swiss pension fund

Configuration

Detailed Breakdown

| Period | Buy-In (CHF) | Compound Factor | After Compounding (CHF) | Tax Saving (CHF) | Compounded Tax Saving (CHF) |

|---|

How it works: Voluntary buy-ins reduce your taxable income in the year of contribution (tax saving). The capital grows tax-free until withdrawal. Upon retirement, the full amount is taxed at a reduced rate. The compound factor shows how each CHF grows over time based on the interest rate.